For my final post in this series, I will turn my attention back to the lady who inspired them – Miss Evelyn Knight – born in England in 1882 and fellow blogger Derrick J. Knight’s great-aunt. She was one of the contingent of British-citizen Baltic States evacuees who arrived in Queensland in December 1940, as a consequence of the Soviet’s grip on power in their former homes in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania (and other affected countries).

Like others, Evelyn needed work, and her profession was teaching. Unable to find anything in city schools, she turned her sights on governess roles in the country. Derrick’s post, quoting from her letter, gives us a good description of her experiences, which you can read here.

The first was on Oona Vale Station in Gooray, near the Macintyre River which demarcates the border between Queensland and New South Wales. This is the kind of country that when it rains, it is reported in the newspaper. It is also the kind of isolated life, that, if somebody went to stay in the ‘big smoke’, or had someone come visit them, that was also newspaperworthy. Gooray is approximately 400 kilometres (250 miles) south-west from Brisbane, and to reach there Evelyn would have ridden the narrow-gauge south-west railway line, leaving Brisbane around 9pm and arriving around 1030 – 1100am the next morning. After her 11 day journey across Russia and Siberia that would have been a walk in the park.

The first mention of Oona Vale Station I find is December 1892, reporting its wool sales. It was then owned by the Evans’. In June 1900, Andrew Fitzherbert Evans announced his wife had given birth to a baby daughter. In 1928 , their daughter Nancy, attended by her sisters Runa and Kitty, married Gordon Saville, of Norwich, England. It was a big affair, covered in detail in a major Brisbane newspaper. This became the Saville family for whom Evelyn went to work as governess in 1941. Saville had taken over running the property when Nancy’s father, Andrew, died a year after they were married. Evelyn left after a year or so, and Mrs Saville frequently advertised for (Protestant) governesses for the rest of the decade. The number of children varied from two to five. It seems it was not only Evelyn who found the conditions trying.

Evelyn’s next position was near Barcaldine. Indeed, she may have responded to an advertisement such as above. Distance-wise, this was even more remote from Brisbane, roughly 1100klm (700 miles) north-west, with a population of around 1500 people, depending on agricultural conditions.

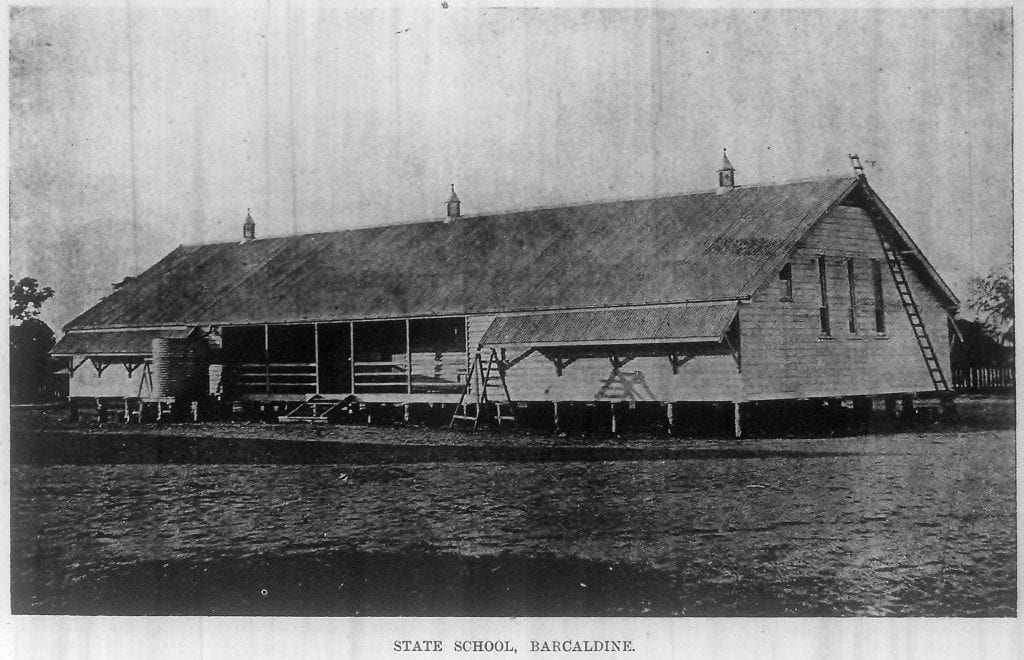

The township had a State School (a somewhat dilapidated building which would be updated in the late 1940s) and a Catholic Convent School. Evelyn doesn’t name the property or its owner, but does say it was six miles away from town. No doubt the children could ride, but being a boy 9 years and a girl of 6, the “rich grazier” obviously preferred they were taught at home. In all likelihood, this was by correspondence (pre-dating School of the Air), with the students following the state curriculum via lessons mailed back and forth (similar to COVID-19 lockdown home schooling). How touching that this young girl stayed in touch with Evelyn Knight for so long.

Although she does not mention it, it is also highly likely Evelyn was expected to help with some of the household duties. This was something that Governesses of the Victorian era – single women from the genteel upper middle-class who had fallen on hard times – particularly objected to. Those financed from the Female Middle Class Emigration Society (FMCES) sometimes wrote back to England horrified in this breeching of social class etiquette.

Between these two assignments, Evelyn mentions living at the Lady Musgrave Lodge. This was established in 1891 to provide temporary accommodation for female emigrants and single women in need of a safe haven. Some letters sent by governesses to the FMCES also decrie the suggestion they should stay in such accommodation because they would need to mingle with those from a lower class. Most wangled the hospitality of the local clergy. Luckily for Evelyn, by the 1940s, such attitudes were on the wane, and I am sure she found respite at the lodge for a minimal expenditure, no matter who were her companions.

As Evelyn says, accommodation was in high demand due to the influx of American soldiers following the bombing of Pearl Harbour on December 7, 1941 and the subsequent outbreak of the “Japanese War”, as she calls it. The below article in The Cessnock Eagle & South Maitland Recorder may have amused New South Welshmen, but I don’t think it would have impressed the Brisbane locals. (Fri 13 Feb 1942, Page 3)

Most other soldiers were much more charming, leading to the oft-quoted complaint of Australian Digger, that their American allies were: “Overpaid, overfed, oversexed – and – OVER HERE!”

At the end of WWII, sixty-three year old teacher, Evelyn Knight, boarded the New Zealand Shipping Company Ltd vessel Rangitata, returning on 26 August 1945 to the London home in Bernard Gardens, Wimbledon, that she shared with her two sisters, Mabel and Ethel. Doubtless the three governesses had many a tale to share with each other.

This series of posts was inspired by fellow blogger Derrick J. Knight, who recently wrote the true-life story of his great-aunt Evelyn Mary Knight‘s escape from Soviet-run Estonia in 1940. This is my seventh (and last) follow-up to the tale. You can read my part one here, part two here, part three here, part four here, part five here, and part six here. Thanks to all who followed along and I hoped you enjoyed this glimpse into how this part of history touched so many lives.

I always feel particularly sorry for folk like Evelyn born around 1882, as they had the misfortune to live through two world wars. All of my grandparents fell into that group, but as they were young teenagers during the First World War they were not directly involved although all remembered it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

These three great-aunts of Derrick Knight’s had particularly curious lives, as all three were governesses/teachers, would have been aware of the Boer War, experienced WWI, had to escape Russia after the October 1917 revolution, and then backed that up by being in the Baltic States when the Soviets occupied in 1940.

None married, and there is probably a logical reason for that. e.g. as a consequence of the “Lost Generation” of WWI.

As well, one was a governess to the young Julie Andrews.

There is a wealth of material there for a novel.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, I think ‘the governess’ has had a hard time through literature as well as real life, and then ending up as you say as part of the lost generation too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a non fiction book on governesses on my bedside table, half finished. It’s something of a rehash of one written a few decades ago, which I had also read. It’s based on actual letters written by governesses back to the Female Middle Class Emigration society. An interesting window into Victorian attitudes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, letters always excellent primary source material and then you have the contemporary fictional versions like ‘Agnes Grey’ amongst many others.

LikeLiked by 1 person

So much of my younger reading days I need to revisit (we didn’t have TV) and then, how am I to fit in the modern authors? Thank goodness I no longer have a job, but still – never enough hours in a day.

LikeLiked by 1 person

There are certainly not.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such an interesting and touching series, Gwen, Thank you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Don.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: A Knight’s Tale (18: In The Bush) – derrickjknight

Thank you so much for this flesh you have added to Evelyn’s story. I am posting a link to this as an addition to mine. Good to read John’s memories, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You are very welcome Derrick, and thank you for the pingback. Good to hear from John, too.

Now, must find another lockdown project …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Enjoyed this ‘mini-series’, Gwen.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Lynda. I had fun researching and writing them, but was a bit worried they were too history heavy for everyone’s taste, so it’s fabulous to have your feedback. xxx Gwen

LikeLike

Thank you Gwen, for this story that plucks some similar chords in my head.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Would you have ridden six miles to school at six years old? Wasn’t sure if I was on shaky assuming these children did not.

LikeLike

I remember riding five miles to the school bus sometimes when I was about nine on my own. Maybe if my brother was with me we would have done it when we were younger. But I only did it on my own if the rest of the us were sick and not going to school that dat.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. (Hope your horse was still waiting patiently when you got back off the bus).

LikeLike

No. I would tie the stirrups up over the saddle and smack her on the tail and she would go home by herself. She may have been needed during the day. Then mum would drive down in the cart and pick me up.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That makes sense!

LikeLike

In lower primary school my mother walked long distance across fields to get to school. She saved the fare money for sweets. Till her mother found out. She still has the concession card.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hopefully your grandmother paid her bus fare AND bought her sweets after that 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

No sweets, Gwen. This is why my mum is scowling in the travel photo. Mum is still a sweet tooth.

🤭

LikeLiked by 1 person